“This article originally appeared on InBody USA and is reposted here with permission.”

Editor’s Note: This post was updated on August 8, 2018, for accuracy and comprehensiveness. It was originally published on July 2, 2015.

There are a lot of great things about calipers that make them convenient. They are relatively inexpensive, portable, and offer you a better assessment of your overall health and fitness than a scale or using an outdated measure like BMI. If the test is completed by a properly trained professional, they’re also a reliable way of measuring body fat change over time.

However, their convenience comes at a cost. If you are using calipers to measure body fat percentage, you should be aware of 4 factors that may affect the accuracy of the results.

#1: The results are heavily influenced by how accurately skinfold sites are located

There are several different methods to perform a caliper test, but one of the more accurate versions is the 7-site test using the Jackson and Pollock equation for body density. The 7 sites on the body are shown here:

Each of these sites must be located precisely on the body, and an X should be drawn on the skin to ensure proper jaw placement. You can’t just eyeball a location; for accuracy, you must take the time to use a tape measurer to locate each site. The abdominal site, for example, is 2 cm to the right of the belly button.

If you have two people with a different level of experience perform consecutive tests on the same person, the chances of getting a consistent accurate measurement drop significantly.

#2: Perfect Technique is Key

Locating each site accurately is only the first hurdle to completing an accurate test. According to the Center for Disease Control’s guidelines for caliper use, not only are there guidelines for locating each skinfold site, there are variances between how the jaws must be placed on each skinfold. These can be only properly placed if each site is marked with an X. However, just placing the X on the skin is only half the challenge.

For example, when pinching the subscapular (shoulder blade) site, the upper jaw must be placed directly on the X mark. This is in contrast with how the jaws must be placed for the tricep pinch; in this case, both jaws must be placed on either side of the X. If these small but critical procedures are not followed, accuracy may drop.

Proper technique extends beyond handling the calipers. For instance, the CDC’s guidelines dictate that a reading can only be taken after pinching, holding, and waiting for three seconds. This allows the skin to compress properly for an accurate reading. Depending on skinfold thickness, taking a reading immediately after pinching can distort the results.

#3: Caliper Results Take Empirical Estimations Into Account, Particularly Age

Calipers use the sum of skinfold measurements to report body fat percentage. But in order to turn the measurements into a fat percentage, two equations need to be used – one to calculate density and one to change density into body fat percentage.

The Jackson-Pollock Equation is frequently used to measure body density and is typically the first step to determining body composition. The equation looks like this (emphasis added):

Body Density = 1.112 – (0.00043499 x sum of skinfolds) + (0.00000055 x square of the sum of skinfold sites) – (0.00028826 x age)

Notice how age is an important variable in the equation. This is a deliberate insertion intended to adjust and increase the equation’s accuracy.

However, by accounting for age, the Jackson-Pollock Equation makes inherent assumptions about the effect age may have on body density, which ultimately influences the final body fat percentage result. These assumptions can misrepresent people who fall outside of normal ranges for their age.

Consider a 50-year-old man, who leads an inactive lifestyle, and has a body composition and body fat percentage that the Jackson-Pollock Equation considers to be average for his age.

Now consider the same man, but assume that he has been very physically active for the entire duration of his life and has more muscle and a lower body fat percentage than your average inactive 50-year-old. His skinfold measurements will obviously be different as well. However, regardless of the skinfold measurements or the lifestyle, both versions of this man will be subject to the same adjustment for age, which will skew the accuracy of the body fat percentage measurement towards what is considered average for a 50-year-old man.

This means that in our example, the inactive 50-year-old man will have results that reflect his body composition, but the very fit and athletic version of a 50-year-old man may have his body fat percentage overestimated because he likely falls outside the average for his age group.

#4 Caliper Equations Also Make Assumptions About Body Fat Distribution

Calipers only directly measure the width of skinfolds; they rely on equations to take this data and turn it into meaningful body fat percentage results. In order to do this, certain assumptions about body fat have to be made, such as how much body fat is due to subcutaneous fat and how much is due to visceral fat.

Today these assumptions can be quite large.

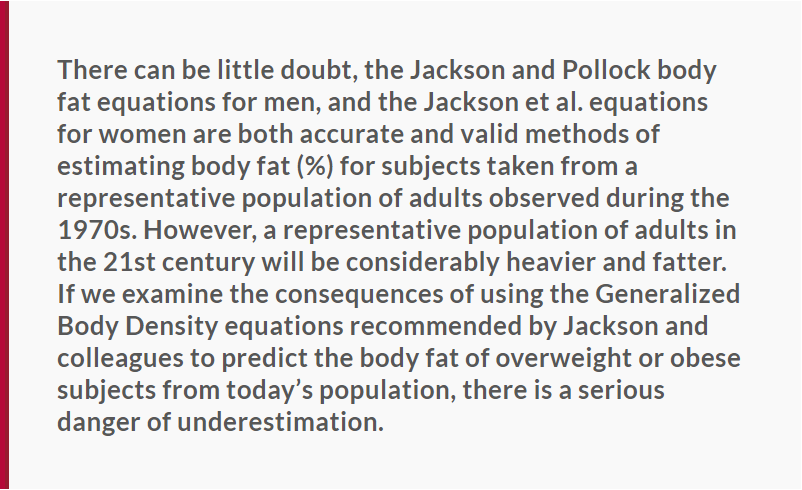

The Jackson-Pollock Equation was developed in the 1970s. Since that time, obesity levels have risen dramatically, doubling between 1980 and 2000. According to the International Journal of Body Composition, this poses a problem concerning the effectiveness of the Jackson-Pollock equation’s ability to produce reliable body density results for modern adults today. The writers argue (emphasis added),

For some people, particularly those who are overweight, relying on this equation may not give a truly accurate result for body fat percentage. And because calipers use this equation, the best they can do is provide an estimation and a potentially unreliable one at that.

But when you’re taking your health seriously, why would you accept an estimation?

Alternatives

Fortunately, advances in technology have made finding precise body fat percentage and body composition results much easier.

For starters, hydrostatic weighing and DEXA scans are both regarded as gold standards to determine body fat percentage/body composition, although securing access to one of these tests isn’t always the easiest or financially feasible.

Among the most convenient and quickest methods to determine body fat percentage are devices that use bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). Although these devices are far more convenient than either of the gold standard procedures, they can range widely in quality and accuracy.

Due to the wide range in quality, the need for precise, medically reliable body fat percentage tests has led to the rise of professional grade BIA devices. These devices employ advanced technology that allows for precise results without any of the inconvenience of the gold standard procedures. They also eliminate some of the drawbacks of calipers, such using empirical estimations that skew results or the need for weeks of training and practice to perform a test properly. And not only can they measure body fat percentage, but some devices give a complete body composition analysis. That means they measure the body’s fat, muscle, and water levels. These medical BIA devices give important metrics like visceral fat, skeletal muscle mass, muscle distribution, BMR, and more. BIA devices go beyond just fat to provide a complete picture of someone’s health, something you can’t do with calipers.

This body composition test was taken on the InBody 770. Click here for more information.

Hopefully, this helps you understand a little more about calipers. Although they can be so quick and simple to use, they do have significant drawbacks when accurate results are essential.

And when it comes to your health, shouldn’t accurate results always be essential?